Prayer, Meditation, and What’s In-Between

Growing up in the Catholic church, prayer was something I heard a lot about. There was the Our Father and the Hail Mary, things I memorized and dutifully recited along with the other churchgoers or my catechism classmates each week. “Lord, hear our prayer” echoed in my mind all Sunday afternoon after Mass, while my individual prayer practice was largely haphazard—when feeling particularly distraught before going to sleep, I might direct my stream-of-consciousness thoughts to God, asking Him to please make everything okay.

In college, I began to explore yoga, mindfulness, and forms of spirituality outside of organized religion. It was during this exploration that I found meditation. I read books and challenged myself to sit quietly for 10 minutes each day, trying to focus on my breath and let go of thoughts as soon as I noticed I was having them.

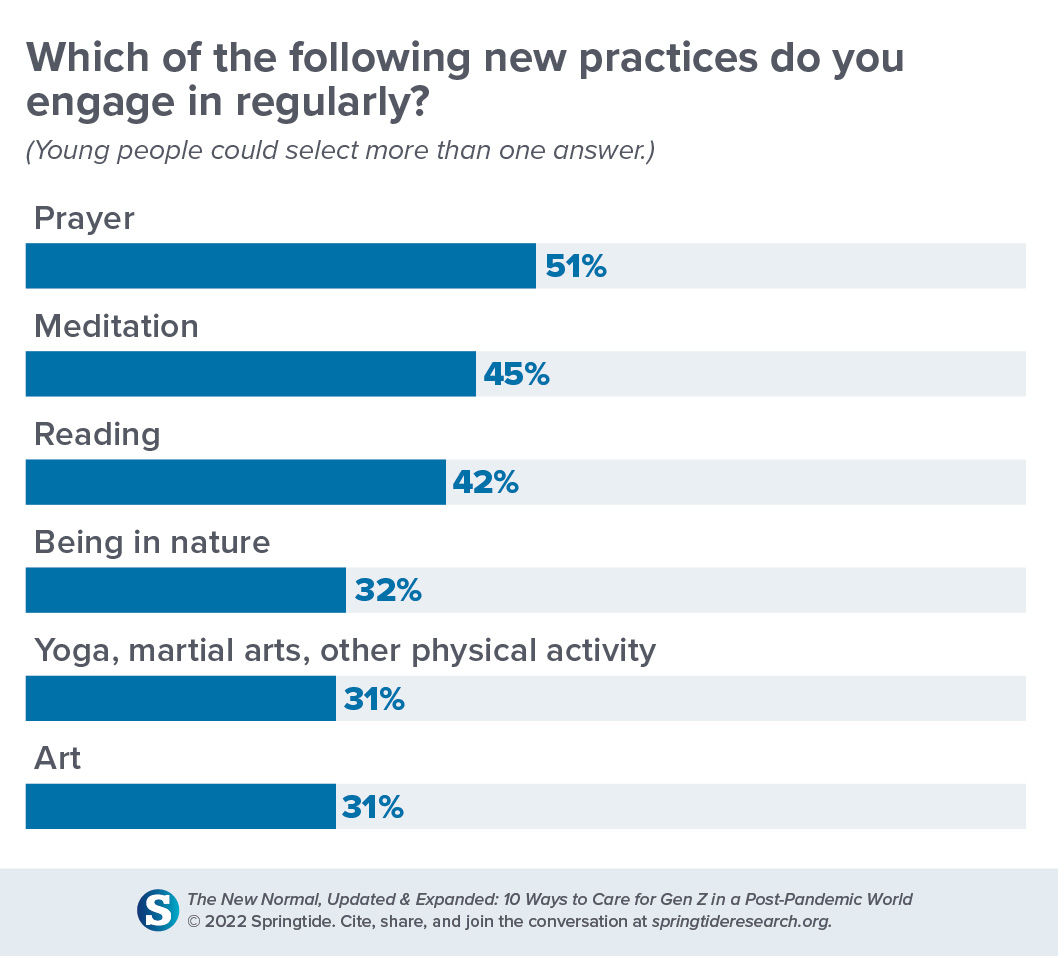

In Springtide’s report The New Normal, Updated & Expanded, young people reported engaging with a host of new spiritual practices since the beginning of the pandemic, the two most popular among them including prayer (51%) and meditation (45%).

In Springtide’s report The New Normal, Updated & Expanded, young people reported engaging with a host of new spiritual practices since the beginning of the pandemic, the two most popular among them including prayer (51%) and meditation (45%).

As I reflect on my own spiritual practices, how they have transformed as I have, how I have experimented and investigated and shifted, I wonder how many of these young people feel like neither “prayer” nor “meditation” perfectly captures what it is they do. For me, I have found something important in the space in between.

I stopped praying the way I did as a child probably around the time I stopped imagining God as a man in the sky. As my conception of the divine changed, so too did my ways of asking it for strength or guidance, or my mode of expressing gratitude for the gifts in my life. Traditional, conversational prayer didn’t feel quite right now that my understanding of the divine wasn’t another person outside of myself, but instead was a quality that permeated everything.

Instead of a man in the sky, I began to see the ways divinity is inherent to the universe and could be found everywhere: I sensed it in the natural world, in other people, and in myself. Prayer, as I was taught, didn’t always allow for this expansive definition of or way of relating to and communicating with the divine.

But while I grew more comfortable setting down traditional prayer, mindfulness meditation was proving to have serious limitations as a channel for spiritual communication, too.

Mindfulness meditation is usually Westerners’ first introduction to meditation, as it was mine. Mindfulness is described by The New York Times as “your awareness of what’s going on in the present moment without any judgment,” while meditation is the “training of attention which cultivates that mindfulness.” There is often an emphasis on focusing on an anchor, such as your breath, in the hopes of quieting your mental chatter.

Lots has been written to suggest that practicing mindfulness meditation can offer an array of benefits, such as stress reduction, improvements in memory and ability to focus, and less emotional reactivity and ruminating. I certainly noticed some of these positive changes in myself once I started meditating. Still, it always felt like something was missing from my practice.

My feelings likely stemmed from the fact that meditation has been increasingly secularized and simplified in the Western world. While meditation’s roots can be traced back to several Eastern religions and philosophies, it’s been watered down as it was introduced to the West, likely to appeal to a wide audience and to ease implementation in school, healthcare, and corporate settings. I sensed that meditating could be more of a spiritual practice—that it didn’t have to feel so clinical and effortful, that there could be more to it than observing thoughts or trying to get rid of them. I just wasn’t sure what that would look or feel like.

I started to get an idea when I was introduced to the Tao te Ching in my final semester of college. It was the required text for a contemplative practices course I was taking (housed in the jazz department, of all places). In the Tao te Ching, a Chinese text written around 400 BC, I found many of the same themes present in mindfulness meditation, such as non-attachment, stillness, and living in the present moment. But there was also a metaphysical quality to the teachings that went beyond mere mindfulness. It invited me to use this practice of non-doing as a vehicle to access the Tao, which translates to “the Way.” In my understanding, “the Way” is synonymous with accessing and harmonizing with the divine.

Here I began to understand how meditation (and other contemplative practices that help me cultivate greater awareness) could be deeply spiritual and not just practical efforts toward improved mental, physical, or emotional health. I started to explore how I could still be in communication with the divine, even if I was not praying in the way I was taught growing up. My new understanding of mindfulness felt less like a closed container and more like an onramp to something more spiritual. In bringing attention to the moment and releasing attachment to my thoughts, I could find a powerful portal to the ethereal realm—a portal fluid enough to align with my new, spacious understanding of the divine and how I might come to know it better.

I’ve been even more encouraged in my spiritual seeking since a few months ago, when I found a community called Inner Sourcing. Inner Sourcing is a monthly series for people in their 20s to virtually meet, go inward through meditation, and connect with spirit. It felt just like something I had been looking for: a ritualized way of marrying mindfulness and conversation with the divine. The Inner Sourcing website says it best: “What we—and many before us—have discovered, is that the practices of meditation, worship, and prayer are not mutually exclusive. In fact, each one becomes more potent when you experience one basic truth: A part of that external power—the one you might pray to, worship, or seek to know—lives in you and wants to be expressed through you.”

Each person’s individual spiritual practices are uniquely personal to them. For me, the word “prayer” has some negative connotations. It can remind me of outsourcing all my own power, but for many others, it evokes profound feelings of comfort and strength. Some people say that for them, prayer is speaking to the divine, meditation is listening. However I experience or connect with it on any given day, I am grateful that when I sit in meditation, write in my journal, walk in the woods, or hug someone I love, I am in communion with the divinity which dwells in the world and in myself.

Hannah Connors is Springtide’s inaugural Writer in Residence. She currently works on a Waldorf Farm in upstate New York.

Photo by Sara Kurfeß